REVERBERATIONS MODULE

Vietnam War

Image credit

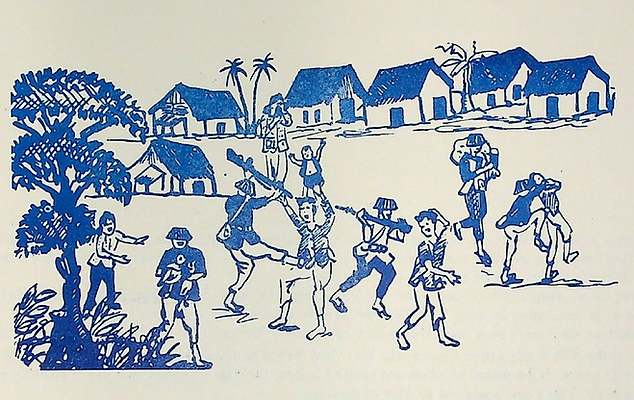

Image: “The ‘Other’ Vietnam Village,” “I Field Force Vietnam, Operation Report Lessons Learned, Tet Offensives Field Force VI, 1 May–31 July 68,” Box 7, Entry (A1)3 U.S. Army Pacific Command Reporting Files, 1963–72, Record Group 550, National Archives, College Park, Md.

Introduction

In the late 1990s, the anachronistic description of Nogunri as South Korea’s “My Lai” signaled the unfolding of something that had been politically impossible throughout the Cold War: namely, South Korea’s belated reckoning with both the civilian massacres perpetrated by U.S. forces during the Korean War and the civilian massacres its forces carried out in Vietnam under the coalitional banner of Lyndon B. Johnson’s “More Flags” program. As a sub-imperial formation, South Korea has been on the receiving end of U.S. imperial violence and it has actively participated in U.S. war aggression against other peoples around the world, including in Vietnam. As South Korean progressive activists have pointed out, South Korea is both victim (피해자) and perpetrator (가해자). Everything that was done to the Korean people by U.S. forces in the name of anticommunism was visited on the Vietnamese people by South Korean mercenaries. Given the entangled nature of South Korea’s accountability, what does justice for the Vietnamese people look like? Can it be achieved without U.S. accountability for its counterrevolutionary violence against the Korean and Vietnamese peoples? Can anti-imperial solidarity be imagined between South Koreans, aligned as they are with a perpetrator nation, and the Vietnamese, as a people victimized by South Korean war violence? What kinds of cross-national and cross-cultural dialogues are necessary between Koreans and Vietnamese citizens–and what can these achieve–particularly in a geopolitical landscape conditioned by South Korean capital investment in Vietnam?

Keywords

Subimperialism

Korea’s “My Lai”

Korea’s “Vietnam”

Cold War “hot wars”

Perpetrator/victim binary

People’s tribunal

Questions

-

Describe a popular image (e.g., a photo, video clip, Hollywood movie scene) of the Vietnam War that you have encountered. Who are the subjects and objects of the violence implied or outright depicted in this image? How does “the ‘Other’ Vietnam Village” image (see below under “Study Materials”) compare or contrast with other visual images of the war’s violence? Based on your analysis, how does the war’s violence work across the “Free” and the “Communist” worlds to complicate the conventional cold war ideological divide?

-

Who had the largest to gain economically from each war? What does your answer reveal about the interoperation of U.S.-led capitalism in the Asia-Pacific region?

-

How does the North and South Korean participation in the Vietnam War broaden our understanding of the hierarchical configuration of national, racial, gender, and class relations in Cold War Asia?

-

For over two decades, South Korean progressives–initially in publications like Hankyoreh 21–have played a galvanizing role in exposing South Korea’s war crimes in Vietnam and in calling for and attempting to enact justice. Yet exactly what justice looks like and how it can be meaningfully realized remain elusive. Strikingly, South Korea’s 2005-10 Truth and Reconciliation Commission excluded the atrocities committed by South Korean mercenaries in Vietnam from its geographic scope. To address that glaring omission, the 2018 People’s Tribunal was convened in Seoul to address South Korea’s criminal role in the Vietnam War. What conception of justice was operative in the People’s Tribunal? Must justice be aligned with state-based redress measures? Are those adequate to the task of achieving justice?

-

To what extent is it useful to consider the Korean War and Vietnam War alongside each other? What does this comparison or juxtaposition reveal? How does this manifestation about the Vietnam War demonstrate the irresolution of the Korean War?

-

Japanese ultranationalist critiques of the so-called comfort women issue have, in tit-for-tat fashion, pointed out the fact that South Korean forces deployed to Vietnam systematically raped, sexually terrorized, and brutalized Vietnamese women and girls. How have South Korean progressive efforts to redress South Korea’s war crimes dealt with the systematic sexual and gendered violence perpetrated by South Korean mercenaries in Vietnam? As part of the pursuit for justice, have there been attempts to address the mixed-ethnic offspring of South Korean soldiers and Vietnamese women and girls?

-

How are binary perspectives, such as perpetrator/victim and colonizer/colonized, myopic in exhuming the full picture of the intermeshed lived experiences of the Vietnam War?

Study Materials

[Article] Jang Han Kil, Asia-Pacific Journal, 17:12:1 (June 15, 2019): https://apjjf.org/2019/12/Jang.html

[From essay introduction] A People’s Tribunal was held between April 21 and 22, 2018 at the Oil Tank Culture Park in Seoul, in conjunction with an academic conference a day earlier organized around the theme of what it means to be a perpetrator of atrocities. In light of the fact that no meaningful action had been taken by the South Korean government in the past twenty years, the People’s Tribunal aimed to re-publicize the issue of massacres committed by South Korean troops during the Vietnam War and to urge the South Korean government to take meaningful reparatory actions for the survivors in legal terms. The year 2018 marked not only the 50th anniversary of massacres committed in Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất and Hà My hamlets of Vietnam, but also the 70th anniversary of the Jeju uprising, bolstering the felt necessity of coming to terms with the nation’s unresolved past.

[Article] Kim, Hyun Sook, “Korea’s ‘Vietnam Question’: War Atrocities, National Identity, and Reconciliation in Asia,” positions: asia critique 9:3 (2001): 621-635

Reflecting the inter-Asia reconciliatory mood of the turn of the millennium, this article delves into South Korea’s belated reckoning–prompted by progressive activist-led investigations into South Korea’s war crimes during the Vietnam War–with its history as a perpetrator of counterrevolutionary, anticommunist violence against the Vietnamese people. Addressing the place of Vietnam in South Korean national history, Kim describes the emergence of a “new language of apology” within the realm of culture--what she dubs “creative acts of contrition” performed by activists and politically engaged artists.

[Article] Kim, Mi-ran, “The Vietnam War and Sexuality: An Analysis of the Images of Ao Dai and Vietcong as Represented in the Media,” The Lines: Asian Perspectives 2 (2011): 83-106

Under the Park Chung Hee regime, South Korea dispatched some 326,000 Korean soldiers to participate in the Vietnam War (1964-1973). Recent scholarship has sought to highlight Korea’s semi-colonial status under the U.S. military, arguing that South Korean economic development was built on its pursuit of “sub-imperialism” in Vietnam. Kim adds a crucial gender analysis to this trend, allowing us to consider how South Korean actions in Vietnam express its subordinate position to American global ambitions while also imposing Korean dominance over Vietnam by perpetrating violence on Vietnamese civilians–particularly Vietnamese women.

[Article] Yoon Chung Ro 윤충로, “베트남전쟁 시기 ‘월남재벌’의 형성과 파월(派越)기술자의 저항: 한진그룹의 사례를 중심으로” (“The Making of a “Wol-nam Chaebul” and Resistance of the Korean Workers with Vietnam War Experience: A Case Study of Han-jin Group”) 사회와 역사 79 (2008): 93-128.

In this journal article, Yoon Chung Ro explores the experiences of South Korean laborers who traveled alongside South Korean soldiers to fight the Vietnam War. Yoon’s article focuses specifically on the experiences of workers for the Hanjin Group. In addition to contextualizing the motivations and hopes of Hanjin workers, the article outlines how they were mistreated by Hanjin and ignored by U.S. military officials. Indeed, the history of Hanjin workers is part of a larger one involving the U.S. military’s exploitation of racialized labor (not only Korean but also people from around the decolonizing world) to wage war.

[News Article] Gluck, Caroline, “North Korea Admits Vietnam War Role,” BBC News, July 7, 2001, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1427367.stm

This brief article spotlights North Korea’s official confirmation that it sent fighter pilots to support North Vietnam during the Vietnam War and it cites Kim Il Sung’s directive, “Fight as if the skies were your own.” On the cusp of the 9/11 era, it describes the warming of ties between North Korea and Vietnam,” with Vietnam’s voicing support of the inter-Korean peace process” that was unfolding between the two Koreas during the “sunshine policy” era.

[News Article] “Korean in Vietnam, Seeing Orphans, Recalls Earlier War,” New York Times, November 21, 1967, p. 4.

In this late 1967 New York Times article, Link White (aka “Chesi”) who served U.S. forces as a child mascot during the battle phase of the Korean War before being adopted by American parents, describes the uncanny experience of being deployed to Vietnam, now as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army. “I volunteered to come to Vietnam,” White explained, “because I wanted to see what kind of war this is in comparison to my experience during the Korean War,” before noting that it was the “same” in its mass production of orphans.

[Documentary] Ghosts of the Vietnam War, London: BBC World News, March 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zixaHx0yPH8

[From BBC introduction] Hundreds of thousands of South Korean soldiers fought alongside the Americans in Vietnam, but the story of South Korea’s involvement in the conflict is largely untold. More than fifty years later, a victim of Korean atrocities travels to the capital Seoul in search of justice. As part of the BBC’s Crossing Divides season, Ly Truong reports.

[Novel] Bang Hyun-seok 방현석, Time to Eat Lobster: Contemporary Korean Stories on Memories of the Vietnam War 랍스터를 먹는 시간, Seung-Hee Jeon Trans. (Honolulu, HI: MerwinAsia, 2016)

Set in a “post”-Cold War Vietnam whose economy is dominated by South Korean conglomerates, Bang describes an uncanny meal shared between a South Korean factory employee and a Vietnamese worker who has been susceptible to both past South Korean war atrocities and ongoing South Korean multinational corporate capitalism in Vietnam. Time to Eat Lobster interweaves the modern histories of Vietnam and South Korea in search for a mutual bond and understanding that cuts across the two countries' shared traumatic past and present battles against war, capitalism, and neocolonialism, with an eye to critiquing South Korean dominance over Vietnam, a unilateralism that exploits the latter’s economic vulnerability.

[Novel] Hwang Sok-yong 황석영, The Shadow of Arms 무기의 그늘 (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2014)

Published in 1985, Shadow of Arms is the first Korean literary novel to critically reassess South Korea’s “economically beneficial” participation in the Vietnam War. This work casts light on what “shadows” South Korea’s modernity: namely, war and imperial economic relations under U.S.-led global capitalism. Through the South Korean protagonist, sergeant Ahn Yong-gyu, who is asked to investigate and thus traverses the impossible-to-control black market of the US military in Vietnam, Hwang unveils the war economy’s facade of development and national profit and asks us to consider what is at stake when South Korea participates in wars waged by United States in Asia.

[Novel] Ahn Junghyo 안정효, White Badge: A Novel of Korea 하얀전쟁 (New York: Soho Press, 2003)

In Ahn Junghyo’s Vietnam War novel, the suppressed horror of the experiences–the killing, the fears, and the mental frustrations–of South Korean soldiers such as Sergeant Han Kiju and Private Pyon Chinsu in the jungles of Vietnam reveal the nature of the psychological and bodily toll of imperial warfare on sub-imperial allies. While White Badge lays bare the futility of war by debunking the Park Chung-hee regime’s master-narrative that “our boys are winning,” it subtly re-endorses military masculinity by sexualizing war killing as “breathless joy” and “ejaculation of male ecstasy.” How is such “war romance” both eye-opening yet problematic?

[Primary Source Document] “I Field Force Vietnam, Operation Report Lessons Learned, Tet Offensives Field Force VI, 1 May - 31 July 68,” Box 7, Entry (A1)3 US Army Pacific Command Reporting Files, 1963-72, Record Group 550

In the Vietnam War, U.S. propaganda leaflets (see “The ‘Other’ Vietnam Village” above) exclusively ascribed violence to its enemy, namely, the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong. Such propaganda constructed and forced an interpretation of the Vietnamese population as victims: the brutalized Vietnamese men, the wailing child, and the helpless woman. The U.S. imperial gaze constructed a cold war orientalist image of the Vietnamese as disempowered. How does this propaganda leaflet distinguish between villagers and the so-called Viet Cong? How does this portrait compare and contrast to iconic Vietnam War images, such as the “napalm girl” photo depicting Phan Thi Kim Phúc, a young girl running away from U.S bombing of a Vietnam village, shot by photographer Nict Ut in 1972?

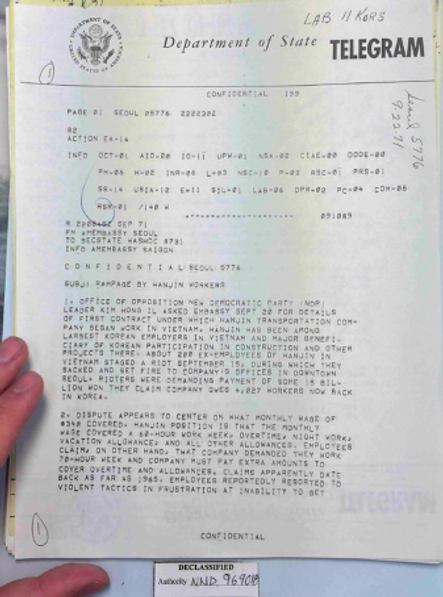

[Primary Source Document] Telegram from US Embassy Seoul to US Embassy Saigon re. “Rampage by Hanjin Workers,” September 9, 1971, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park.

Written by Deputy Chief to the U.S. Operations Mission (USOM) to Korea, Francis Underhill, this telegram describes protests by Hanjin workers that resulted in the burning of an office building occupied by the Hanjin Group. The event was the culmination of years-long efforts by Hanjin workers to receive back pay from the company. Workers and company security clashed, leading to the destruction of the company offices. While seemingly an objective accounting of events, it is important to note the language used to describe the actions of Hanjin workers. For instance, the terms “rampage” and “rioters” (similar to descriptions of Saigu) are used to describe the actions of the Hanjin workers. The provocative language belies the loyalties of U.S. officials in their interactions with foreign corporations and foreign workers–they prioritized the needs of the former.